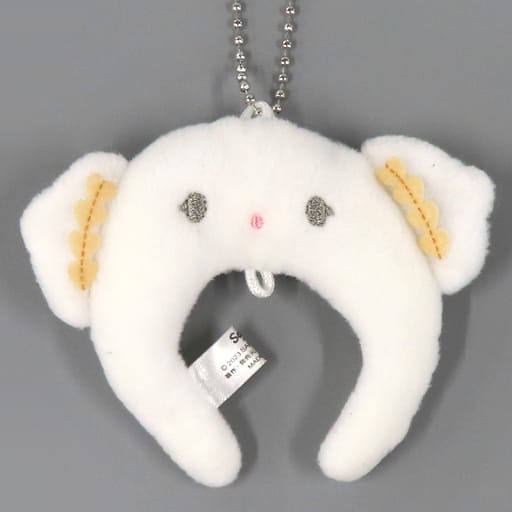

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ A B BOX ボックス フルコンプ

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ A・B BOXセット

未開封A・B ボックスセット

ボックス未開封のまま匿名配送いたします。

【A】

・こぎゅみゅん

・ハンギョドン

・ポムポムプリン

・けろけろけろっぴ

・マイメロディ

・シナモロール

・バッドばつ丸

・ハローキティ

【B】

・タキシードサム

・あひるのペックル

・ポチャッコ

・マイメロディ

・ぐでたま

・シナモロール

・クロミ

・リトルツインスターズ

バラ売り不可

新品ですが、自宅保管になりますので気になる方はご購入をご遠慮ください。

喫煙者・ペットはおりません。

即購入していただいて大丈夫です。

ただし、発送方法や商品の状態などの質問は、購入前にお願いします。

マスコット 限定 グッズ ハローキティ キティ

ハローキティー マイメロディ マイメロ

シナモロール シナモ シナモンロール シナモン

クロミ マロンクリーム ポムポムプリン

オタ活 サンリオ エンジョイアイドル

ぬいぐるみ コスチューム マスコット ホルダー

ポチャッコ ハンギョドン ピアノ キティちゃん

キキララ ばつ丸 フルコンプ 全種類商品の情報

| カテゴリー | おもちゃ・ホビー・グッズ > おもちゃ > キャラクターグッズ |

|---|---|

| 商品の状態 | 新品、未使用 |

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ | 2015年12月出産☆シルバニア

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ ハロウィン 全8種 コンプリート

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ | 2015年12月出産☆シルバニア

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

サンリオ - サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ ハロウィン A B

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ | 2015年12月出産☆シルバニア

サンリオ シークレットミニカチューシャ | 2015年12月出産☆シルバニア

サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB | サンリオオンラインショップ

サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB | サンリオオンラインショップ

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

2023年最新】シークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

クロミ シークレットミニカチューシャ MIX B

サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB | サンリオオンラインショップ

2023年最新】ばつ丸 カチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

2023年最新】シークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

駿河屋 -<中古>こぎみゅん 「サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニ

2023年最新】シークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

サンリオ - クロミ シークレットミニカチューシャ MIX Bの通販 by A's

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

2023年最新】シークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

6ページ目 - サンリオ カチューシャ キャラクターグッズの通販 1,000点

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

2023年最新】シークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム - メルカリ

楽天市場】サンリオキャラクターズ シークレットミニカチューシャB

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

2023年最新】サンリオシークレットミニカチューシャの人気アイテム

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています